ABOUT THE PROJECT

The project's main goal is to study the rural environment of the northern most of the three Dacian provinces, Dacia Porolissensis. This covers many aspects, in the registries of settlements, people, economy and production, supply and, not last, the military, which is the dominant factor on the Dacian northern frontier. The aim is to obtain a functional model of the deployment, function, structure and supply methods of the Roman rural food enterprises. The idea of this project came in the context in which qualitative research of the Roman society is prevailing in the international academic milieu, trying to decrypt issues more and more enigmatic, as it is the food supply. Roman agriculture, and implicitly food supply was a matter of very small importance in Romanian archaeology, this being one of the departments where we practically are significantly left behind. In the Romanian (and Dacian) particular case, we have bad state of research. It has tended to focus on military and urban sites, where clear traces of urbanization are recognizable and easy to present in a festive manner.

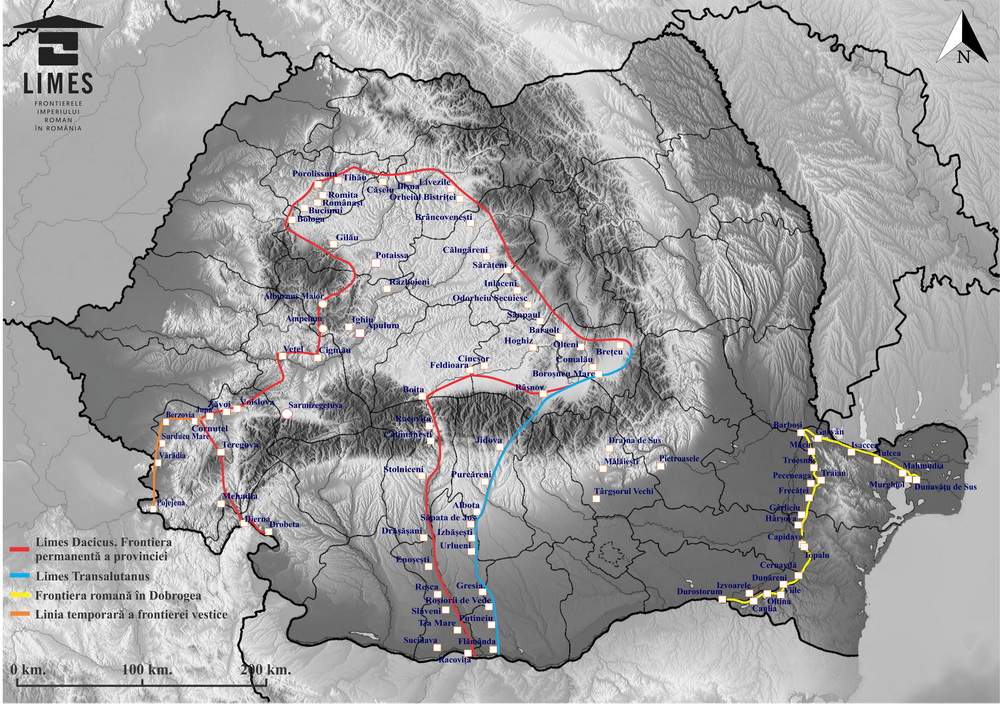

Fig. 1 - Dacia Map (National Programme LIMES)

Fig. 1 - Dacia Map (National Programme LIMES)

In this regard, the more archaeological approach that we propose will have also its limitations. Reliable archaeological evidence itself is very limited, as only about 10% of the total reported sites have been investigated, and not even those in a satisfactory manner. Excavation however, is not our approach. We are proposing an entirely non-invasive investigation, that will stretch on different departments, from field-walking and geophysical surveys to epigraphic analyses. The modern methods of remote sensing, beginning with aerial photography and satellite imagery, till the more thorough and resourceful methods of geophysical surveys and palynological anaiyses, can offer us a great deal of information on these remote and forgotten sites. The final effort will be made to put all the information together in an attempt of developing an extensive rural map of Dacia Porolissensis.

History

The overwhelming importance of agriculture in Roman economy is generally recognised. Most of the wealth of the Roman society came from this, but actual information on yield on capital is scarce (presumed 5-6% in Italy). Most of the information we have from Italy (Varro, Columella or Cato the Elder), presenting us a land of cereal crops and arboriculture, mixed, unlike Africa, where cereal crops were widespread. It is commonly acknowledged that Roman agriculture was essentially primitive, being based on the two-field system of alternate crop and fallow. The natural conditions of Italy lead to an obvious association of two agricultural approaches: intercultivation of sown and planted crops and pastoral husbandry. Mixed intensive farming is based on the commonly accepted model of self-sufficiency, of a farm of about 100 iugera. Even with the expansion of the latifundia, farming habits of the traditional Roman land owner have not disappeared.

Fig. 2 - Cato the Elder (234 BC - 149 BC) - Patrizio Torlonia

Fig. 2 - Cato the Elder (234 BC - 149 BC) - Patrizio Torlonia

Fig. 3 - Pliny the Elder (19th century impression)

Fig. 3 - Pliny the Elder (19th century impression)

Fig. 4 - Collumella - De re rustica, 1564

Fig. 4 - Collumella - De re rustica, 1564

In the matter of agricultural organization and types of estates, there is much confusion and shallowness, for example in the discussion of latifundia. The size of a farm is not only determined by its acreage, but also labour and capital invested in it determine its size as an agricultural enterprise. In ager Veientanus, Italy, villas concentrate along the roads and isolated farms are placed deeper in the hinterland. As far as size is concerned, the differentiation is made between small units (10-80 iugera), medium-sized units (80-500 iugera) and large units (over 500 iugera). According to the management, four systems are in evidence: (1) direct labour by the proprietor and his family; (2) direct supervision with a slave manager and slaves working; (3) working by shares, the owner and the tenant (colonus); (4) leasing of the farm on a cash-rent basis. In regard to the systems of production, six types of farms are known: the vineyard (vinea), the olive plantation (oletum), the suburban farm (praedium/fundus suburbanum), the mixed farm, the large ranch, the unit specialized in husbandry and steading (pastio villatica).

Fig. 5 - Ploughing

Fig. 5 - Ploughing

Fig. 6 - Picking Fruit

Fig. 6 - Picking Fruit

Fig. 7 - Roman mosaic, putting bread into the oven, 1st half 3rd CE, from a series showing agricultural work throughout the year, from Saint Romain-en-Gal, France.

Fig. 7 - Roman mosaic, putting bread into the oven, 1st half 3rd CE, from a series showing agricultural work throughout the year, from Saint Romain-en-Gal, France.

Fig. 8 - Vendanges Romaines, Cherchell

Fig. 8 - Vendanges Romaines, Cherchell

The farm buildings vary widely and are built according to utility, in general. They are composed of, but not limited to rooms, kitchen, manager's quarters, rooms for processing wine and oil, storage facilities, processing yards.

The Roman expansion carried with it huge economic implications, amongst them being also the disposal of the acquired territory. In Egypt, for example, taxes on land and the products of farming contributed over 60% of state revenues, apparently. The reallocation of land to subjects was the key moment of the transfer from military control to civilian rule and was often accompanied by land survey. The reality of Roman farming in the provinces was a bit different from the theoretical information that we get from the writers in Italy. Although we can detect the formation of great estates in many regions, coupled with the emergence of the 'villa economy', there are several instances of crop specialization: wine in Fayoum and southern Gaul, olive oil in Spain or North Africa. The temperate zone would profit from the better rainfall ratio, and excel in cereal cultivation, vineyards (now extensively extended towards north), and stock raising for meat and other secondary animal products. Beer producing and use of animal fats was a cultural marker of the north. North Africa had two crucial regions for the feeding of the city of Rome: The Nile delta and Tunisia - both intensively cropped with cereals; the rest of the land being massively used for olives.

Fig. 9 - The Roman Empire (FRE Culture 2000 project)

Fig. 9 - The Roman Empire (FRE Culture 2000 project)

Objectives

Any discussion of the subject involves basic questions concerning demography, social organization and nature of production: (1) How densely was the countryside populated? (2) What was the social structure of these populations? (3) What were they producing? (4) How were the consumers (military or civilian) supplied? The Roman provincial economies may have been built on the labour of lots of peasants, but they were dominated by the output of the bigger players, and major estates were a fact in most of the provinces. They could be extremely large in scale and rationally organized so that profitability and costs could be assessed adequately and tied into wider commercial networks.

- The drawing of the map of the Dacia Porolissensis' countryside. The database that will result from the project will contain several categories of information: topographic coordinates of every site identified, aerial photography, land-level imagery, results of geophysical surveys, results of field-walking and field evaluation. The database will serve as the main support for the map, which will be systematized according to each category of information. It will undoubtedly serve as one of the most valuable work-instruments for researchers interested in Roman countryside from Romania and elsewhere.

- The identification of the systems of production, market and supply. Archaeobotanical and paleontological studies attempted in the areas of a representative sample of sites will allow us to establish in an acceptable regard, the crops cultivated in the area surrounding a rural settlement or villa. Results of this kind can be very useful for the understanding of local production and dispatch (see Cavallo/Kooistra/Dutting 2008). Secondly, a detailed topographic/archaeological study on the Roman roads in the region, including slope and accessibility analyses, would provide us with the opportunity to find the main commercial ways in the region, especially in regard of food supply. The distribution of the sites identified, on the above-mentioned ranks can also reveal us the focal points of the provincial economy, meaning local centres and markets.

- The registry of people living/working in the countryside of Dacia Porolissensis. In this sense, epigraphic evidence would have to be reassessed, in the sense that we will have to clearly draw the line between the countrymen and the town people. As much of the evidence comes from the rural settlements in the vicinity of forts, some of which later became urban, it will not be an easy task. However, the opportunity to identify the main agents in this field, either landowners, tenants (coloni), estate managers (vilici), specialized workers, employed slaves, or tradesmen is a most satisfactory reward, and we will gladly pick up the challenge. These people will also be part of the database, tagged and placed spatially as individuals, as to be able to best integrate them in the system.

- The supply of the military on the northern frontier. Even if this could apparently be a different matter, the two are organically connected in this region of the Empire. Dacia itself, and more so its northern most province, are deeply dominated by the military milieu, in such a way, that one could argue that the entire province was established and developed as to serve the immense number of military deployed north of the Danube. Much of Dacia Porolissensis' infrastructure was created depending on the frontier and to serve for its best supply. First and most important settlements came into being in the vicinity of the forts, and, when the military control impeached their further development, they extended outside, by doubling the settlements or obtaining pre-urban or even urban status for themselves. Therefore, it is not an aspect we can ignore, not even neglect. It is a fact that the almost 15,000 military men deployed in this small province would have to have a significant impact on local economy, especially food production. This objective will materialize in an extensive supply map of the northern Dacian frontier.

- A general/synthetic look on the provincial rural economy. The completion of the previous objectives will provide us with the necessary skills and instruments to be able to present, as the conclusion of the project, a synthetic work on the economic mechanisms of the countryside of Dacia Porolissensis. This has never been attempted before in Romanian academic environment, but we believe that our skills and equipment, along with the re-evaluation of the past results make us the best candidates to depart in such an endeavour. This result will weight heavily in Romanian historiography and will be an important achievement, able to stand at the level of the Western state of the art.

- Dissemination, clustering, aftermath. It is for the first time that such a research project in the matter is being proposed. From this perspective, the impact of the results will be all the greater when taking into account the project manager's scientific visibility, which should enable the further dissemination of the results and further possible collaboration. We intend to focus the publication of the results of the research primarily in Europe, towards the periodicals in the German and British academic milieus, and thus to come into contact with those researchers who are interested in similar subjects. Through the balance of senior researchers, post-docs and doctoral students, we will be able to form a team and create an environment which is well-suited to the passing on of the experience of scientific work, as well as ensure that the young researchers will develop their skills and competencies in this field. We must underline the team's multi-lingual composition as well as the different areas of research from which the researchers com from - the best ingredient for actual interdisciplinarity. Finally, this research project will attempt to be a model that could be applied in all the Dacian provinces and spawn spectacular results. The economic history of Roman Dacia is an 'untouched treasure' from this point of view, and surely, the success of this work will provide the motivation for further such endeavours.